St. Thomas More Church History (1936-1986)

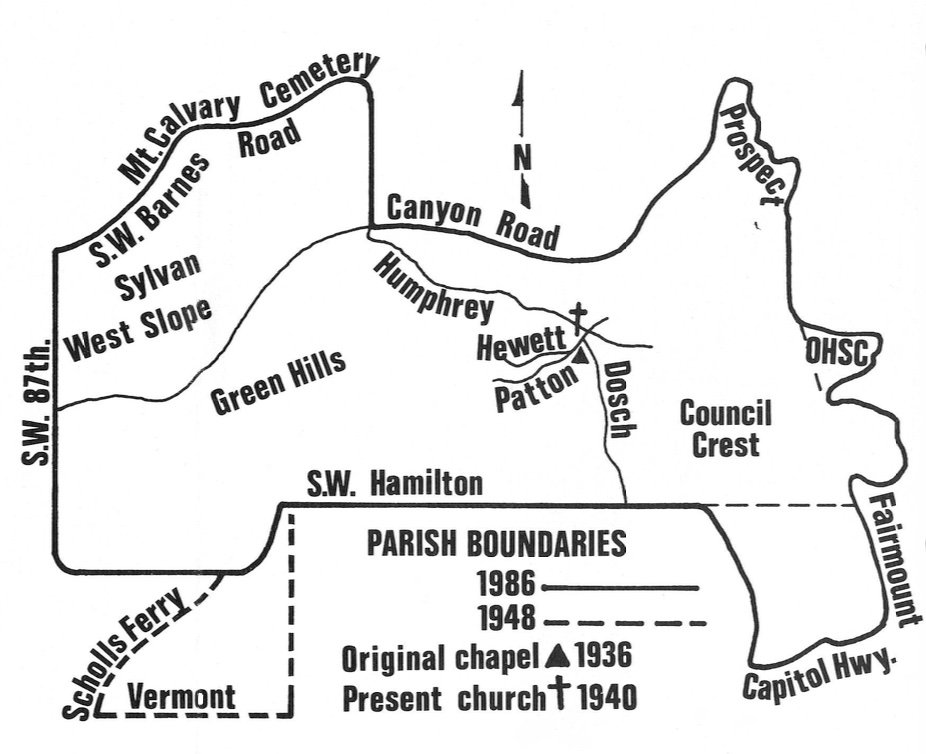

Introduction: The excerpt below is a lightly edited portion of a pamphlet celebrating the 50th year anniversary of the St. Thomas More Church (1936-1986) - although this portion mostly only covers events to the opening in 1936. The church is now located in the SW Hills Residential League neighborhood as is the ground of its predecessor, the 1883 Mt. Zion Congregational church, which had been situated across the street (SW Patton Road) in what is now the church parking lot, at the corner of SW Patton Road and SW Dosch Road.

Bridlemile is located just to the west of the church parking lot. Its ties to the church are that the Kelly family (same as in Bridlemile’s Albert Kelly Park) gave the name “Mt. Zion” to this original community. Also, “Edward Rogers” was an original pastor for the 1883 Mt. Zion church. “Edward Rogers” was also the name as the second owner of Bridlemile’s Tigard-Rogers House. He bought it in the mid-to-late 1870’s. Perhaps, they were the same person.

At the Crossroads

To the earliest inhabitants of the area, it was known as the Hills of the Tualatin Indians. According to legends, these natives held religious ceremonies called Councils on the summit of the Tualatin Hills. The ceremonies were held on a sacred area set aside exclusively for the Council. For reasons of secrecy, privacy, visual observations and religion of the tribes, they were usually held on the highest vantage point. Thus, the Crest, or uppermost prominence or peak of their Council ground was probably the most strategic and sacred area and as such was respected as a sanctuary which housed their “altar”. And, like the spires of a church overshadowing its community, the totem of these natives rose above and protected the Council gathering.

Fiery signals from the summit summoned the natives in the area to Council and from all directions of the compass they forged trails through the Tualatin Hills until they converged into a crossroads which took them to the Council’s Crest.

During the 1830’s, however, their villages were devastated and depopulated by epidemics of smallpox, measles and cholera; forcing their few surviving members to relocate to the Tualatin Valley beyond, near Wapatoo Lake. Later they were removed to the Grande Ronde Reservation. Abandoned native trails in the Tualatin Hillls became overgrown with vegetation.

In the next decades, American pioneers began arriving in the area, settling first around the ferry stations of the Willamette and Columbia rivers. As the Tualatin Hills were fast becoming the “hub” of a growing timber business, they became known as the West Hills of Portland.

Overgrown Indian trails were reshaped by the first pioneer homesteaders and the Congregational Church played an important part in establishing a new religious character in the West Hills area. Among the first to establish a land claim in the area now called Green Hills was Deacon Hamer (Homan) Humphrey. Arriving in 1849 he joined fellow-Congregationalists John Talbot and Matthew Patton. Another early homesteader was German-born Presbyterian Henry Dosch. Where their claims adjoined at the crossroads of Humphrey, Talbot, Patton and Dosch, they formed a junction and in 1862 a one-room meetinghouse and school was built and called Mount Zion, Oregon.

Other Congregation communities were also being established in the valley around Wapatoo Lake, in such place-names as Tualatin (Forest Grove), Wapatoo (Gaston), Gales’ Creek, Hillside, Yamhill and Sheridan.

But it was a Methodist minister, Rev. Clinton Kelly and his brother, who about 1860 had given the appellation of Mount Zion to the West Hills community. For sentimental attachments for his family home near a Mount Zion meeting house in Kentucky, and for Biblical reasons, the crossroads and its surrounding area became known as Mount Zion, Oregon.

After considerable religious interest was found to exist among the community members, in 1879 a Congregational mission was organized at the meeting house and Rev. Edward Rogers of Beaverton was secured as its pastor. A collection among the members was taken up and a Board of Trustees purchased land across the Dosch Road junction from the meetinghouse. There, they constructed the Mount Zion Congregational Church.

On January 3, 1883, where Dosch and Patton intersected, a 24’ x 30’ chapel was built and dedicated as Mount Zion Congregational Church; among its early members, trustees, delegates and teachers were the families of Humphrey, Talbot, Patton, Jeffcott, Prince, North, Rogers, Gaston, Harer (O’Hara), Hewett and Strohecker.

The community of Mount Zion was not exclusively composed of Congregationalists, but was a heterogeneous one, and its crossroads were traversed by its diversely different ethnic neighbors as well.

At the crossroads of Green Hills in the 1890’s with one of the lovely estates in the background, an equestrian group meets in the Hills. Center photo: the crossroads in 1941 (OHS).

Note: the maple tree behind the riders is the same tree in the cover painting, now grown up and in front of the church. The Natt McDougalls are among the riders. Marian McDougall-Heron photo

Patton’s Pass was the main arterial connecting Dosch Road to the German, Swiss and Bavarian communities of Hillsdale, Shattuck and Metzger. Other roads continued to the stage and ferry stations at Boone, Taylor and Scholls.

Patton also ran down the southern slopes of the West Hills to the Jewish, German, Slavic, Italian, Irish and Croatian neighborhoods around Slavin Road and Portland. It also connected with Humphrey’s road and Talbot, the former reaching Tanner Creek (Canyon Road) to the communities of the Congregationalists in the Tualatin Valley; the latter continuing up to the summit of the community. The summit itself changed in name from Talbot to Beale, then Glass Hills, for its various owners until 1898.

Geo. Himes, official publisher for the City of Portland and the Congregational Church, the promoter of the West Hills development over that of Mount Hood to the east, had led a group of Congregational Delegates, then meeting in Tualatin (Forest Grove) at the National Convention there, to the summit of the West Hills.

He described the historical-religious association of the area with the original Tualatin Indian and associated the word “Council” as being also Congregational in nature – that is, the word Council described their church’s formal meetings. Thus, he suggested it would be most appropriate to name the summit of the West Hills, Council Crest.

And so it came to pass that Council Crest was named, an area overlooking the misnomered “Mount” Zion, which was in reality a pass in the summit.

Neither was it the only “Zion” in the area. An eccentric bachelor named Nathan Jones had, in 1850, purchased a land claim near Deacon Humphrey and built himself a home, called it, “The Hermitage.” Its outside walls were painted with bizarre scenes depicting his own version of a future “Zion Town” he hoped to develop in the West Hills.

Besides “The Hermitage” his claim contained a blacksmith shop, two stores and a saloon – which did not bode well with his Prohibitionist neighbors! Deacon Humphrey, also a freight wagon hauler, refused to haul away Jones’ empty beer kegs from the area, and no doubt tensions between the two “Zions” existed.

Deacon Humphrey was also a strong advocate of strict observation of the Sabbath as a day of rest, which was also at odds with promoters like Himes, who were attempting to develop the Council Crest area into a tourist attraction.

Rev. Atkinson, who was pastor of the First Congregational Church in Portland and who had early-on conducted Sabbath worship in the Mount Zion meeting-house before the chapel was built, had, in 1883, predicted that “time would show the strength of Mount Zion.” But due to several factors, the little chapel’s strength was one of invigoration and impotency.

There were internal difficulties in maintaining itself financially, and it was irregularly served by Congregational ministers from Hilldale, Beaverton or Hillsboro. The chapel was often abandoned for long periods of time, with a school and youth group struggling in the community meeting-house to survive. Outside elements contributed to its ailments as well.

Portland was becoming a city of immigrants and often conflicting social, economic and religious issues. Established Portland families of wealth and influence were at odds with this massive influx of newcomers, and they began buying large tracts of land in the West Hills area, relinquishing their previous estates to the ethnic communities.

The West Hills now became known as Portland Heights and the rustic pioneer character of the Mount Zion community was becoming displaced into an area of spatial houses and beautifully landscaped estates – not to mention one of much social prestige.

By 1887 religious work in the little chapel was at low ebb. Deacon Humphrey died that year and was buried in the little community’s cemetery – called Jones’ cemetery (presently behind the Metro-Baptist Church in Sylvan). Grand estates being built near Humphrey’s home include those of Capt. Cochrane, a steamboat man, and Henry Hewett, related to the Gaston and Patton Congregationalist families in the Tualatin Valley. While across the street from the Mount Zion community and school hose was the summer residence of the Labbe Bros. of Portland (west of St. Thomas More Church).

The area was indeed changing. Hewett’s road, which paralleled Humphrey’s, now turned Mount Zion’s crossroads into a five-fingered intersection which ended at the little chapel. For a while it appeared that new life was breathed into the church in 1888 when Hewett donated a bronze bell from the wrecked ship, “Yaquina” for its steeple. And, when the cable car line finally reached the Heights from Portland in 1890, Hewett also donated a public boardwalk from the cable station to the crossroads.

But, despite the convenient location of the chapel at the crossroads, with its new bell and boardwalk, for both religious and social reasons, the new residents of the area preferred to by-pass the little chapel and continue up the boardwalk to the park at Council Crest. On Sunday, they preferred to walk or take the cable car to the more majestic churches in the city below – most of which had been established and supported by their pioneer families.

Mount Zion in 1907 from Council Crest view. Note the chapel’s steeple, and barely-visible is the meeting-house cupola. Large estate on hillside is seen also in picture behind equestrian riders.

Thus, by 1893, after a long period of abandonment, lacking financial and membership support, without a pastor, Sunday school, youth group and no services of any kind, Mount Zion Congregational Church officially closed.

The following year the eccentric Jones died of a brutal beating after selling a portion of his property – after which he had refused any medical treatment of any kind – except whiskey! He was buried in Jones’ Cemetery where Deacon Humphrey lay at rest – albeit at extreme opposite corners of the grounds – and shortly afterwards, “The Hermitage” burned down.

The Trustees of the Mount Zion Congregation Church were still looking for a new site for a new church. Also so, by petition of their few remaining members to the city of Portland Jones’ “Zion Town” became officially named Sylvan. Today, only Zion Addition and Jones’ Addition (which contains Zion Street) in Sylvan are dim reminders of poor old Nathan Jones.

Sylvan, it was noted in the official minutes of the Congregation Church, was a “new and friendly community, of Christian spirit and unity and harmony, and was the only church and school in the neighborhood; neither over-crowded, nor dominated by other denominations, rivals or sects.” This would indicate that there had indeed been religious rivalry in the old Mount Zion – Portland Heights area, but to what extent it is not known.

Strong population drifts as mentioned were accompanied by strong religious denomination changes and shifts as well. And, it was, in the turn of the century, an era “anti” and “nativist” movements – events which would resurface in the 1920s into a much stronger and violent nature.

But by 1905, these milder effects overtook the new Sylvan Congregational community and its church became officially dropped. Attempts to revive Mount Zion were made in 1913-14 and again in 1920-26, but a World War and renewed ethnic hostilities and religious prejudices undoubtedly left the “strength of Zion” powerless to revitalize itself.

The meeting-house became a “mom and pop” variety store and gas pump station. The chapel, although retaining its name Mount Zion Congregational Church and its legal title still held by its Trustees, remained abandoned and neglected – becoming deteriorated with time.

With the West Hills becoming a popular tourist and residential attraction, old pioneer claims were platted and subdivided, their old rustic homes torn down and replaced with grand estates, and a new era was beginning at the crossroads.

Mount Zion became platted Greenway (1905) and Green Hills (1913) by the Patton, Hewlett and Gaston families, and Council Crest became officially named in 1906. Street names, however, capture part of that early pioneer-religious association for the names are not only site visible from the Heights, but reflect the native and Congregational influence as well in such names as: Tualatin, Wapato, Yamhill, Sheridan, Chehalem, Gaston, Hillside, Hillsboro, Beaverton, Gales Creek, Hamer, Prince, Himes, and of course the historic crossroads of Humphrey, Patton, Talbot, Hewett, and Dosch.

During this time there were Catholic families scattered throughout the West Hills area. The nearest Catholic facility was either the Cathedral or the chapel in the old St. Vincent Hospital in N.W. Portland. They had expressed a desire to locate a Catholic Church in the Green Hills area as early as 1920.

But the population and related religious changes, which had affected the character of the area in the past, was now reaching into another era, one of revived “anti” and “nativist” movements which included burning fiery crosses on all the summits surrounding Portland and with rumors of the “pitiful Catholic children” being buried in the West Hills’ (Mount Calvary) cemetery.

Before his death in 1925, Archbishop Alexander Christie had tried to find a church for these West Hills families, but the “anti-Catholic” movements of that decade were of more pressing concern.

Other denominations, especially those with private schools of their own to consider, were tending to support the Catholic position during the time the Ku Klux Klan movement in Portland support the passage of the School Bill of 1924, which was directed against Catholic teachers and Parochial schools.

Portland’s Congregational Church denounced the School Bill, declaring that, if the Protestant majority of Oregon disregarded the rights of the Catholic minority, they were guilty of tyranny. But political, religious and ethnic differences and tensions prevailed and the School Bill passed.

Struck down by the United States Supreme Court in 1925, the School Bill and its related “anti” movement generally paved the way for better understanding between those afflicted by its events. A year later, Edward D. Howard became Archbishop of Portland and again the families in the West Hills sought his attention to acquire a Catholic church in the area.

Mount Zion chapel, Oct. 29, 1935, about the time Fr. John Laidlow toured the Green Hills area in search of a Catholic Site. (OHS/Oregonian)

High up on Green Hills, on Arthur Way, was the home of Thomas and Polly McArthur. Polly had been a recent convert to Catholicism and was a very vocal and apostolic Catholic; convinced that the Holy Spirit had commissioned her to promote the establishment of a Catholic parish in her area. She was a valiant and persevering woman. Archbishop Howard was to have no peace until this was accomplished. This time, however, another devastating era was on the horizon: the Great Depression.

The peculiar geographical position of the area made it very hard to find a location site that would be accessible and convenient to all the people. Moreover, until a full evaluation of the need and support for such a church was warranted, it was impractical to assume a great burden of debt for such a construction project until its success was clearly demonstrated.

It was 1935. Pope Pius XI had just canonized Saint Sir Thomas More, and it was the peak of the Depression, with WPA workers laboring for $65 a month on the roads surrounding Portland Heights. In late 1935 Father John Laidlaw was appointed by Archbishop Howard to tour the West Hills area extensively in search of a site for a church.

The Archbishop’s car, which Fr. Laidlaw was driving, was in need of much repair, and Divine Providence saw to it that the car should stall at the crossroads of Patton, Humphrey, Talbot and Dosch roads in Green Hills. There, between Dosch and Hillside, reposed the deteriorating remains of the old abandoned Congregational church. Its sills were rotted, the windows broken and the roof leaked. Youths in the area had used it as a sort of shelter, lighting fires in its old wooden interior.

Father Laidlaw saw the possibility of it serving as a temporary church for the 25 or so Catholic families in the area, and the head office of the Congregational Conference was contacted about the possibility of using the property for a few years as a Catholic facility.

In December 1935 when the officers of the Conference were approached on the matter, they showed themselves extremely courteous and quite willing to permit its occupancy for at least a year without rental for the repairs which would be made to put the premises in reasonable order. In February 1936 they returned with a favorable response to the Archdiocese and even suggested that they would be willing to arrange its sale on satisfactory terms if both parties were in agreement. Later, because the cost of such reparations were so extensive, the period of rent-free conditions was extended to three years.

Early in March 1935 Archbishop Howard had invited priest from the Cathedral and laity of Green Hills to meet at his home on S.W. Myrtle St. to discuss the possibility and advisability of the use of the Mount Zion chapel. Among those present at the meeting were Revs. Francis J. Schaefers and John R. Laidlaw, Mr. Joseph Healy, Mrs. Wm. Healy, Mrs. Phil Parrish, Mr. and Mrs. Roland Prentys, Mrs. E. G. Shonenback, and, of course, - Hrs. Polly McArthur.

Dan Malarkey, a Catholic who lived in the area and a building contractor, began restoring the building, while several more meetings at various homes resulted in the gathering of $700 to pay for the restoration of the chapel.

Among the donors for the St. Thomas More Church were the Strohecker Bros., a pioneer family who began as wagon halers to the early Mount Zion homesteaders and were later Trustees of the Sylvan Congregational Church. In 1902 they established their historic Strohecker market on S.W. Patton Road, and throughout the years have remains patrons and supporters of the Catholic parish. Armond Strohecker in 1950 secured the heirs of the Mount Zion Congregational Trusteeship and deeded the property to the Archdiocese of Portland; later himself becoming a Catholic convert.

Thus, on June 21, 1936 the first Catholic service in the former Mount Zion Congregational Church was offered.

Ca. 1880. The crossroads of Mount Zion, Oregon. Meeting-school house on the left and the Mount Zion Congregational chapel on the slopes of Dosch and Patton Roads. (OHS)

Patton road with Mt. Zion (aka St. Thomas More) chapel on Dosch and variety store/gas pump at the crossroads. 1941. (OHS)