Subdivisions and Additions

Bridlemile contains at least 52 sub-divisions and/or additions. Most of them came into being after World War II.

What is a Subdivision?

A typical sub-division is a plot of land, like a farm or an estate, that a land developer has purchased, upgraded with utilities and streets, and divided into lots, which are sold to individual home buyers.

"Subdivision" means the division of a lot, tract, or parcel of land into two or more lots, plats, sites, or other divisions of land for the purpose, whether immediate or future, of sale or of building development. It includes resubdivision and, when appropriate to the context, relates to the process of subdividing or to the land or territory subdivided.

Source: Subdivision (land) - Wikipedia

Typically, homes in a subdivision are mostly built around the same time, using similar construction techniques, of roughly similar design styles and are sold to buyers from similar socio-economic groups.

An addition typically refers to land added to an existing piece of land (e.g. to a subdivision).

What Do Sub-division Streets Look Like and Why?

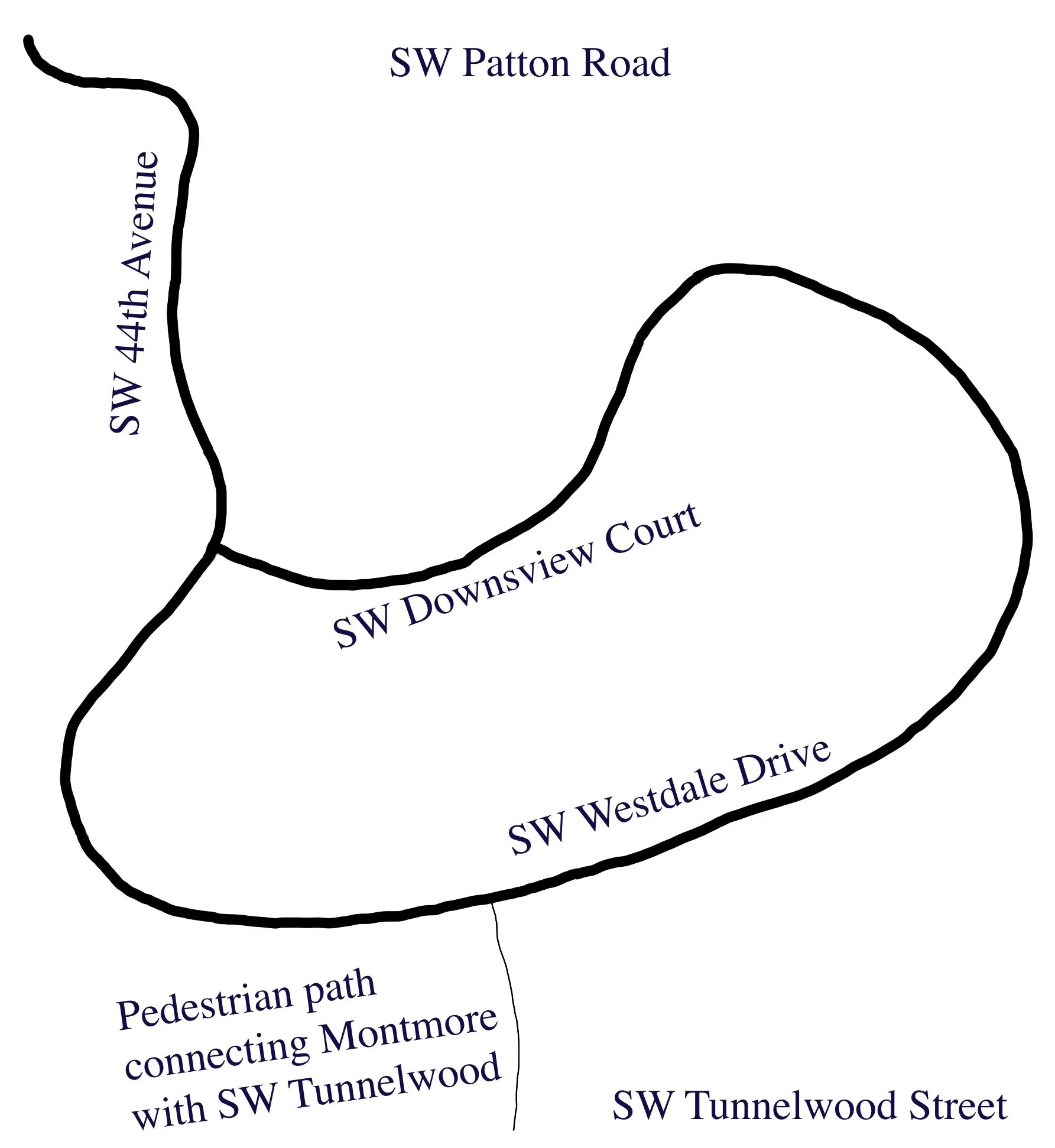

Above: Bridlemile’s subdivision streets tend to be either curvilinear with cul-de-sacs (e.g. Bridlewood) or loops (e.g. Montmore).

Above: In contrast, Portland’s downtown and inner east-side’s streets are laid out in a grid pattern.

Curvilinear streets and cul-de-sacs, like those in Bridlemile’s post-WWII subdivisions, work to slow down vehicle traffic and so reduce noise and improve safety by, among other things, reducing traffic to mainly local vehicles. Also, it reduces street racing.

In contrast, Portland’s 19th and early 20th century city planners laid out streets, like those in Portland’s downtown and inner east-side neighborhoods, in a grid pattern, with straight streets placed at 90-degree angles to each other. This strategy supported the use of street cars. Private cars did not yet exist back then - or were relatively rare.

Why Do Subdivisions Look the Way They Do?

First, the US government’s Standard City Planning Enabling Act (SCPEA) of 1928 set the stage for the control of private subdivision of land – and for planning commissions.

For more information: Standard State Zoning Enabling Act and Standard City Planning Enabling Act

American Planning Association

Second, Federal Housing Administration (FHA) guidelines largely defined the post-WWII standard subdivision appearance.

The Great Depression, starting in 1929 and extending into the 1930’s, slowed the market for residential and commercial real estate development. New housing starts declined by 92% from 1928 to 1934. Banks were reluctant to extend new mortgages in such a down and risky market.

Congress addressed this with the National Housing Act of 1934. That act set up the Federal Housing Administration (FHA), which provided insurance for lenders. That, in turn, made mortgages safer investments for the banks. It also encouraged buyers by extending the mortgage time from as short as five years to 30 years and reducing the down payment required for buying a house from between 30% and 50% down to 20%.

The FHA strove to improve the safety of its mortgage insurance program by creating guidelines for developers of new housing subdivisions that dictated subdivisions be created of a high-quality level – and, thus, be relatively safe investments.

They set minimum standards for items like plumbing and foundations.

In addition, they called for land-use planning that focused on designing neighborhoods for cars, which in that time period were quickly gaining in popularity. Automobile planning included inclusion of curvilinear streets and cul-de-sacs rather than the up-to-then popular grid-pattern street design.

When Was Bridlemile’s Subdivision Housing Built?

As shown in the above bar chart, a boom in subdivision housing took place between about 1946 and 1995.

In 1946, developers started building homes in NW Bridlemile’s Orchard Park subdivision (29 homes). They used a loop street design and were all or almost all one-story ranch-style homes with one or two car garages. Average size was 1,690 square feet. Average year built: 1948.

In the mid-1950’s, the Brookford (120 homes) and Doschdale (64 homes) developments, with curvilinear street designs, added more homes in south-east Bridlemile, south of SW Hamilton, west of Dosch Road, east of SW Shattuck and north of B-H Hwy. Many were located around Albert Kelly Park.

In the late 1950’s and early 1960’s, the Bridlemile subdivision added 132 homes in NE Bridlemile and the Wilcox Estates subdivision added 154 residences in NW Bridlemile. They featured curvilinear streets, cul-de-sacs, and loops.

The 1960’s and later saw the Smoke Rise development with 64 homes in NW Bridlemile, north of SW Hamilton and west of SW Shattuck. It featured six cul-de-sacs and no easy through streets.

In the early 1970’s, Bridlemile continued to grow, especially with the Bridlewood (103 homes) and Montmore subdivisions (72 homes). The Bridlewood subdivision incorporated curvilinear street design, Montmore used a one large street loop design.

Into the 1980’s, as the amount of undeveloped land decreased, the number of homes in each new subdivision also decreased.

Pedestrian Walkways

While FHA-approved subdivision designs include streets designed to limit local vehicle traffic, they also call for pedestrian paths to let walkers to bypass the limited access roads and more easily reach outside destinations.

“A walkway is any type of defined space or pathway for use by a person traveling by foot or using a wheelchair.” Federal Highway Administration - Walkways

Bridlemile pedestrian pathways include:

1. The SW Julia Court pathway connects SW Julia Court and the rest of east-side Bridlemile (including Bridlemile school) a relatively safer to reach SW Shattuck Road near SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway. The associated pedestrian crossing at SW Shattuck Road also helps.

Bridlemile Walkway: A Portland in the Streets Project

2. The SW Westdale to SW Tunnelwood pathway gives NE Bridlemile a walking route to Bridlemile school and neighbors in SE Bridlemile – and on to SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Hwy. However, it could use improvements to deal with land erosion.

3. The SW Stonebrook Drive pathway connects east Bridlemile and Hillsdale residents with Albert Kelly Park.

4. The SW Lowell Court to SW 48th Place pathway/bridge connects NW Bridlemile residents with Bridlemile School and northeast Bridlemile.

5. The SW 55th Place pathway connects NW Bridlemile (at SW 55th) with SW 54th Drive and from there people can walk on to SW Hamilton and Bridlemile school.

It could use a bridge to better facilitate walking across the resident creek - especially in the rainy season. A long-time resident said that a bridge once crossed the creek. However, in the early 2000’s it was falling apart. The city inspected it and declared it was too dangerous as is. The city removed it shortly thereafter.

6. The SW Hamilton to SW Seymour pathway gives NW Bridlemile residents a safer alternative to SW Beaverton-Hillsdale Highway than walking on SW Hamilton and SW Shattuck. A spur path connects this path to the Hamilton Crest subdivision.

7. The SW Tunnelwood to SW Tunnelwood walkway in NE Bridlemile lets walkers stay on track despite a short break in the SW Tunnelwood roadway. Motorized vehicles wanting to continue on SW Tunnelwood have to take a several block long detour.

8. The SW Windsor Court walkway on SW Windsor between SW 57th and SW 58th in NW Bridlemile lets walkers stay on track despite a short break between SW Windsor and SW 58th. Motorized vehicles wanting to go from SW Windsor from SW 57th to SW 58th have to take a long detour.

9. The SW 34th Avenue to SW Jerald Way path gives pedestrians in far eastern Bridlemile a way to walk to Hamilton Park and Bridlemile School that does not require them to trek along busy and sidewalk-less SW Hamilton Street.